Tutorial: Create 360 Degree Videos in After Effects with Skybox

Pretty cool demonstration of Mettle Skybox.

Pretty cool demonstration of Mettle Skybox.

Check out this introduction to CamSphere, an fulldome After Effects template/workflow from Dom St-Amant of SAT, using a six-camera rig. I’ve worked with multiple camera rigs in AE before, but this looks really smooth and well packaged. Really eager to see how it all works.

Update 5/25/15: CamSphere V2 is available for purchase: details here.

Update 8/27/17: Check this out: Thomas from the Czech Republic wrote me with his new app (his first!) that takes care of it all, on Mac or Windows. Visit istreetview.com, and navigate the familiar Google Streetview interface to find your pan, and the appropriate Pano ID. Up at the top right is a “Download 360°” link – which will take you to download his app. From there, copy and paste the Pano ID code into the app, pick a destination for your file, and download. That’s it! It even handles some of the pan formats I’d been having trouble grabbing.

Update 8/20/15:AHA! So a lazy evening taking a look at Google Maps API examples again, and I’ve sussed out a way to display the PanoID as you move around the map. Take a look and don’t mind the ‘undefined’ when you first load. As soon as you move to a new location, it’ll get replaced by the PanoID.

As I’ve mentioned in the comments below, there are some panos that just won’t work and will return black frames. These appear to mostly be user-submitted panos. Scenes from the Google Car generally seem to work.

In other words, I should probably heavily edit this post someday.

Update 7/23/14: If you look carefully around the new Google Maps, there is an option for “Return to classic Google Maps” so all is not lost. There are probably some ways of doing this with the new Maps also, but I haven’t sorted out a simple way yet.

Update 3/24/14: Well, it appears that the new version of Google Maps uses URLs that make it harder (if not impossible) to discover the individual tile addresses – so this has as far as I can tell stopped working. I’ll poke around and see if there’s something new in the Maps API, but for now, I think this doesn’t work anymore. Phooey.

—

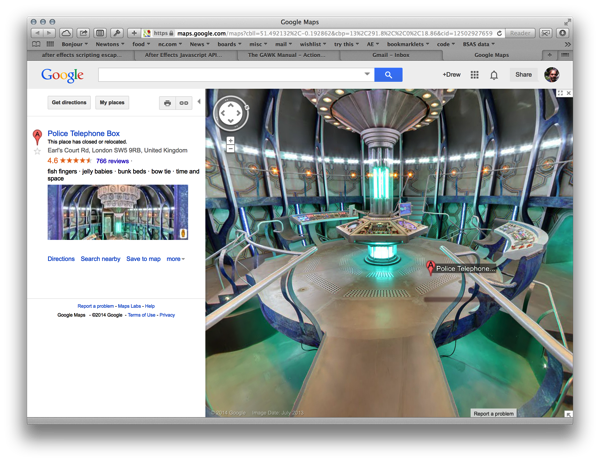

A couple weeks ago, I had the task of turning our dome into the inside of the TARDIS from Doctor Who. (Planetariums are bigger on the inside too, right?) A few days before I had stumbled on this awesome Google Streetview easter egg that puts you right inside the control room of the blue box itself. Step inside and take a look around!

There are some really nice, high resolution spherical views in there, and I want to get at that data. But how?

So you’ve got 60,000 4K frames that someone needs resized to 2K. It will take an eternity to do it with Photoshop, even with a batch action. Fortunately, hidden within Mac OS X is a much faster utility, and it will take care of every file in a folder with just one line of code. (Or three, depending on how you count.)

It’s called SIPS (“Scriptable Image Processing System”), and it’s built in to every Mac OS since (I think) OS X 10.3. If you’re not familiar with the Terminal in OS X, it will take a little bit of study and practice to get it. You should at least be familiar with the Terminal commands cd and ls, and navigating folders with these commands, before proceeding.

If you were just going to use SIPS to convert the size of a single image, you might issue a command like this, having first used cd to navigate to the folder containing the image:

$ sips --resampleWidth 2048 bigfile.png --out smallfile.png

(Don’t type the $ at the beginning of the line!)

Try it out on a file, substituting the names of the input file bigfile.png and the output file smallfile.png for names of your choosing, and substituting the output size 2048 for whatever you like.

Things get a little more interesting if you want to do a whole bunch of files at once. We’ll have to issue a SIPS command for every file in the folder:

$ for i in *.png; do sips --resampleWidth 2048 $i --out Converted;done

With this code, SIPS will run once for each file ending in .png found in the current folder, and save a resized copy into a folder called Converted (which in this case, you will have to have created within the current folder).

Give it a shot, and you’ll be amazed at how quickly SIPS can churn through files.

You can specify the input and output folders without having to navigate with cd:

$ for i in /path/to/inputfolder/*.png; do sips --resampleWidth 2048 $i --out /path/to/outputfolder;done

What are the paths to the folders? Try navigating with cd to the folder you want and type pwd. Or, if you’re feeling like a cool trick, drag the folder icon in the title bar of a Finder window, and drop it into the Terminal window. Terminal will instantly type for you the proper path of the folder opened in that Finder window. Clever!

You can also use SIPS to convert file formats, but I’ll let this article cover that. Don’t miss the comments for a useful tip.

I’m not sure how clearly I wrote this, so if stuff isn’t making sense, please shout at me in the comments and I’ll do my best to clarify. Always have a backup before you experiment and mess with your precious files!

A tutorial! Finally!

In my efforts to put up a video podcast tutorial – my first – I’ve so far discovered that I talk too much. Or at least, I wrote too much for me to easily speak without making more voice stumbles than I’m comfortable with. Further, my ability to read and talk and point and click at the same time is severely limited. I never got more than five minutes into a take before realizing how much editing I’d have to do just to get it presentable, and – long story short – many months of procrastination ensued.

So instead I’ll be putting all the details in text, and below you’ll find a quick bare-bones video that just gives you the step-by-step process. One of these days maybe I’ll find my voice for smooth off-the-cuff podcasting. It will take some practice. I’ll even one day record an introduction that doesn’t include an apology for the overall roughness of the finished product. Am I overthinking all of this? Yup. – Drew

So it’s not all that exciting an effect, but I’d like to share the first thing I do whenever I start a new fulldome project in After Effects, which is create the dome frame – the border that defines the circular shape of the fulldome image. (I suppose the word ‘frame’ could be a little confusing because it could also refer to a single frame of animation, but I’m sticking with it anyway. If there’s an ‘official’ name for this thing I’d be curious to know. I looked in the draft specs of the IMERSA standards document and didn’t see it specifically referenced, so maybe there isn’t yet a name.)

The dome frame is the topmost layer in any fulldome project. It helps us determine where the edge of scene is while we’re animating, and masks out anything that falls beyond. Plus, without it, you risk having a little bit of video data spilling over the edge of your dome, if your projectors aren’t perfectly masked off.

The dome frame also happens to provide a handy place to put some metadata about the show: the frame number and time code, the name of the show, your logo, and so on. Added bonus: if you put all of these layers together into one comp along with your audio track, you won’t have to worry about syncing audio with your time code again. Trim or move the dome frame comp around all you like – it won’t matter, your time code and your audio stay together.